Exponential innovation has shrunk the shelf life of technical skills, and the ability to map, track, and deploy talent based on actual capability rather than just job titles has become a competitive necessity. In fact, organizations that successfully adopt skills-based practices are 63% more likely to achieve their business goals.

Additionally, 38% of companies expect to use a single, enterprise-wide skills library. Yet mapping these skills to individual visible profiles remains a challenge, thanks to a lack of a common language. This article explores what a skills ontology is, its key components, and how you can build one to realize the full potential of top talent and fill critical roles.

Contents

What is a skills ontology?

8 components of a skills ontology

Skills ontology vs. skills taxonomy: What’s the difference?

How to build a skills ontology framework in 9 steps

6 real-world skills ontology examples

Key takeaways

- A skills ontology is a structured ‘map’ that defines each skill, captures how skills are interrelated, and how they apply to projects and roles.

- Unlike a taxonomy, which is a simple hierarchical list, an ontology is a dynamic network that supports ‘intelligent’ AI-enabled HR tech that can infer hidden talent.

- Building a successful framework starts with a clear business problem, piloting a single ‘job family’, and establishing strong governance to keep data accurate.

- Moving to an ontology-based model shifts HR from reporting on current skills to predicting the skills you’ll need in the future.

What is a skills ontology?

As business needs change faster, organizations are moving from fixed job descriptions to a skills-based approach. To manage this shift, HR needs a shared skills ontology to standardize how the company defines and uses skills.

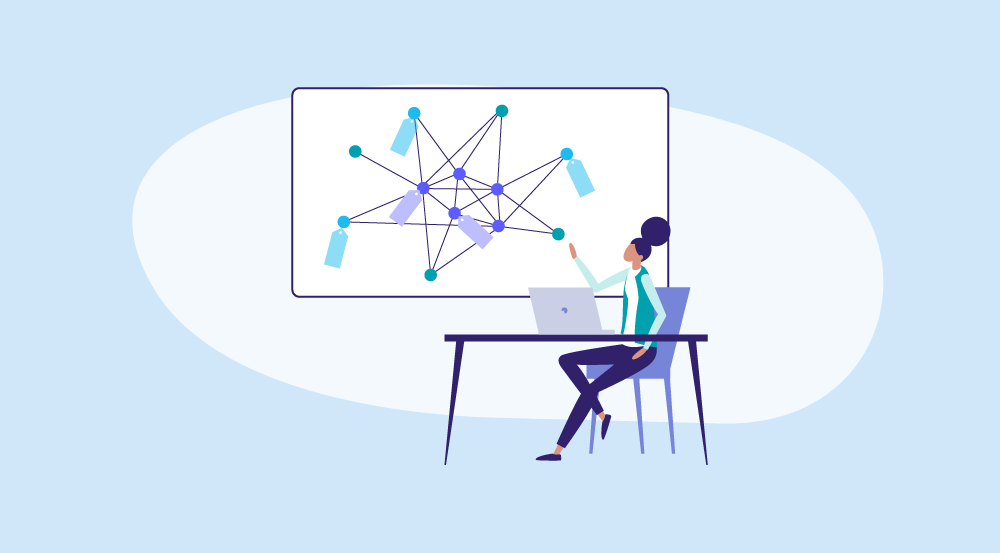

A skills ontology is a structured map of skills. It defines each skill and shows how skills connect and apply at work. Unlike a basic taxonomy, which lists and groups skills, an ontology captures relationships between skills.

For example, a Content Writer may already have skills like research and SEO. If the company needs a UX Writer, the ontology can identify an 80% skills match and help you target upskilling to close the remaining 20%, fill the role faster, and support career growth.

The goal is to create a shared language across the talent life cycle, so hiring, learning, mobility, and workforce planning all use the same definitions. HR drives this by setting direction, defining real-world proficiency levels, linking skills to roles, tasks, and tools, and keeping the ontology accurate as needs change.

8 components of a skills ontology

In some organizations, talent data is trapped in silos. For instance, one manager may refer to a skill as “client relations”, while another calls it “account management”. This makes it challenging to know what your people can actually do.

To build an effective system, you must look beyond the list of names. The primary objective is to create a standardized language for talent that allows you to predict future needs, bridge capability gaps, and enable internal mobility. A robust skills ontology consists of the following eight essential components, which turn raw talent data into actionable business insights:

1. Skills entities

Skills entities are unique identifiers or skill names. Some examples include ‘Figma designing’, ‘UX writing’, or ‘user research’. Standardizing these identifiers or names is the first, crucial step toward integrating data across disparate HR information systems (HRIS) and applicant tracking systems (ATS) platforms.

2. Definitions

Every skill requires a clear description of its place in your specific organizational context. To make them effective, publish these definitions in a centralized, company-wide directory. This ensures every department works from the same ‘dictionary’, and creates consistency in performance evaluations and hiring.

3. Relationships

In a skills ontology, relationships define how different skills connect to one another. By mapping ‘skill adjacencies’, you can more easily identify the most suitable internal positions or candidates for lateral mobility. Examples of skill adjacencies include how UX writing relates to Figma proficiency and how SEO relates to keyword research.

4. Skills hierarchy

A skills hierarchy is the ‘parent–child’ structure within a skills ontology. It groups broad skills at the top of the hierarchy, then breaks them into more specific sub-skills in the layers underneath. An example of a skills hierarchy could be: digital marketing → SEO → keyword research / technical SEO / on-page optimization.

5. Proficiency levels

When using a skills ontology model, you would define skill proficiency levels on a scale from beginner to expert. It should also include observable behaviors and provide employees with a transparent roadmap to support career pathing, as well as personal and professional learning and development (L&D).

6. Skill evidence signals

These are validated ‘proof points’, e.g., certifications, work outputs, or assessments — you would use to verify that a person possesses particular skills. This enables your HR team to make more objective, data-driven talent decisions, supporting fairness and minimizing discriminatory talent practices.

7. Context tags

These link skills to the real world by tagging them to job families, tasks, or tools. For example, you might tag the ‘UX writing’ skill to the ‘product development’ job family, the task of ‘interface localization’, and the tool Figma. Doing so helps ensure your skills ontology remains operational and reflects actual day-to-day work.

8. Governance rules

Governance rules provide a framework for maintenance in a skills ontology. These rules typically define who should approve changes and the process of updating the system. Strong governance helps ensure the ontology remains a trusted source of truth and stays up to date with changes to the business.

Master skills-based practices to benefit your organization

Learn how to spot skills gaps and fill them, map the skills your workforce has and needs, and develop a skills ontology and framework to drive business success.

With the Talent Management & Succession Planning Certificate Program, you will learn to:

✅ Create a skills-based talent map using a skills-focused approach

✅ Develop a strategic talent management framework to create clarity

✅ Use capability and skills maps to determine talent demand

Skills ontology vs. skills taxonomy: What’s the difference?

When discussing skills-based organizations, the terms ‘taxonomy’ and ‘ontology’ are often used interchangeably, but they serve different purposes. A skills taxonomy is primarily a categorization system, like a structured list. A skills ontology, however, is much more sophisticated — it adds meaning, complex relationships, and rules to that structure.

Structure

A one-dimensional hierarchy with a parent-child structure. A skill typically sits in one ‘branch’ only (e.g., ‘content writing’ comes under ‘marketing’ and nothing else).

A multi-dimensional network that covers lateral and complex links. A single skill can belong to multiple categories and relate to diverse tools and tasks simultaneously.

Meaning

Relies on a literal label for definition. It assumes the term is self-explanatory or applies identically across all roles and departments.

Defines not just the skill, but how it behaves in different scenarios. It understands that ‘public speaking’ for a CEO differs from that for a teacher.

Flexibility

The structure is rigid and static. Adding new skills to it often requires creating entirely new categories or silos.

Embraces fluidity and adaptivity to easily map new connections. If a tool like ChatGPT emerges, it can be instantly linked to existing skills like ‘copywriting’ or ‘programming.’

Use cases

Its administrative and descriptive nature makes it best for cataloguing training courses, simple keyword filtering in an ATS, or high-level organizational reporting.

Enables predictive AI to infer ‘hidden’ talent, suggest highly relevant internal moves, and identify ‘skills gaps’ before they become critical.

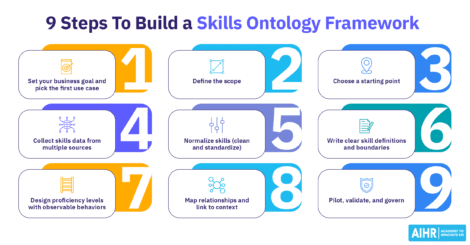

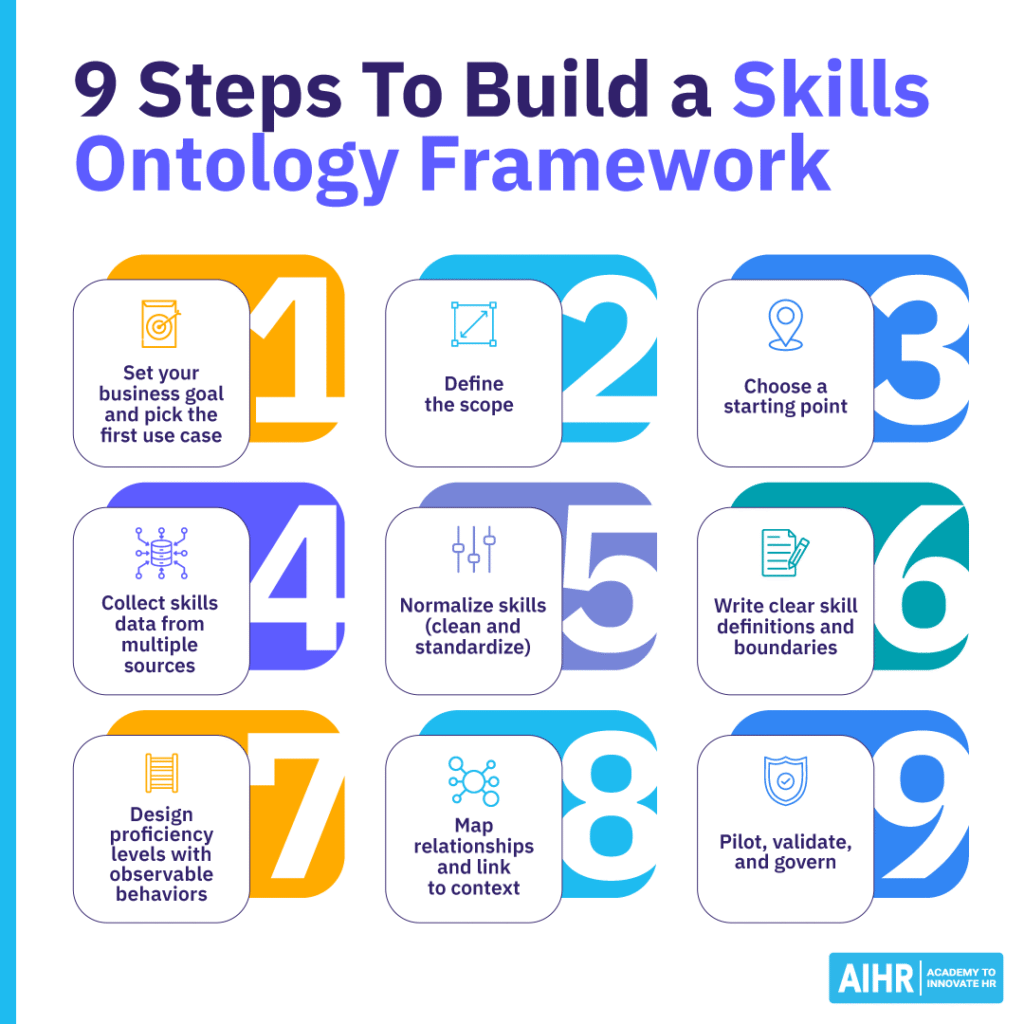

How to build a skills ontology framework in 9 steps

Transitioning to a skills-based model is a significant undertaking. To ensure your skills ontology framework is both practical and scalable, your HR department should follow a phased, methodical approach. Here’s a nine-step guide to help you:

Step 1: Set your business goal and pick the first use case

Identify a business pain point that a skills-based approach can solve. For example, you might focus on internal mobility to fill talent gaps from within, or skills-based hiring to reduce reliance on degrees. Before starting, define how you’ll measure success. Consider KPIs like reduced time to fill, increased internal fill rate, or improved training effectiveness scores.

Step 2: Define the scope

Start with a pilot segment to test and refine your methodology. Choose a single job family to focus on, such as sales or a critical domain currently undergoing change, like cybersecurity or AI ethics. Set boundaries by deciding exactly what’s ‘in scope’ in terms of specific roles, geographic locations, and seniority levels you’ll include in your initial framework.

Step 3: Choose a starting point

Deciding how to source your initial list of skills is a critical strategic choice. Building everything from scratch is an option, and while time-consuming, it does offer 100% organizational relevance. Another option is to leverage an external public library, such as O*NET or specialized vendor lists, to build faster and customize as you go.

Step 4: Collect skills data from multiple sources

To build a realistic skills ontology map, you need to look at how work is actually done in your business by gathering data from:

- Historical job descriptions and top performers’ résumés

- Performance criteria and reviews

- Project histories

- Your learning management system (LMS)

- Direct input from subject matter experts (SMEs) and manager interviews.

By noting duplicates and inconsistent naming at this stage (for instance, ‘client management’ versus ‘account management’), you’ll save time during normalization.

Step 5: Normalize skills (clean and standardize)

Establish a naming convention to keep your system consistent, then merge synonyms by consolidating variations like ‘presentation skills’ and ‘presenting’ into a single skill entity. Split overly broad skills into actionable components (e.g., split ‘data’ into ‘statistical modeling’, ‘data cleaning’, and ‘SQL querying’). Finally, remove overly vague skills like ‘hard worker’ or ‘team player’.

Step 6: Write clear skill definitions and boundaries

A skill name alone is open to interpretation, so you need definitions to provide the necessary guardrails. Write each definition in a concise one-sentence format, followed by a “What it is / what it’s not” section to ensure clarity and prevent scope creep. Additionally, add specific practical examples of tasks or work outputs that demonstrate the skill in action.

Step 7: Design proficiency levels with observable behaviors

To clearly distinguish levels of expertise, avoid vague labels, and focus on evidence. Use a scale with three to five levels and describe exactly what performance looks like for each grade. Keep definitions role-agnostic where possible to enable better comparison across departments, but allow role-specific context tags when a skill manifests differently in a specialized role.

Step 8: Map relationships and link to context

Map the relationships between skill entities (e.g., knowing ‘cloud architecture’ implies a relationship with platforms like AWS or Azure), and you’ll transform your list into a true ontology. Link skills to specific tasks, tools, and roles within your scope. Then connect your learning resources to specific skills and proficiency gaps, so the system can recommend the right course at the right time.

Step 9: Pilot, validate, and govern

Before a full-scale rollout, test your system under real-world conditions. First, launch your pilot to run the framework in your chosen job family. This helps test if the skills-matching works for recruiters and if employees find the proficiency levels intuitive.

Establish a permanent governance structure that defines who owns the ontology, its review frequency, and the process for employees to request the addition of new skills. At the same time, ensure effective change management to drive true adoption. Roll out your system with targeted training for managers, so they understand how to use the ontology in day-to-day decisions.

6 real-world skills ontology examples

Here are six ways organizations are currently using skills ontology frameworks to drive business performance:

Example 1: Enterprise skills platforms

- Many large organizations deploy AI-driven talent platforms (e.g., Gloat or Eightfold) that maintain a dynamic skills graph

- These platforms use skills ontologies to power internal mobility by automatically recommending roles or projects to employees based on their inferred skills and career aspirations.

Example 2: Public standard frameworks

Here are three established public frameworks your HR team can use as a foundational starting point:

- The Occupational Information Network (O*NET), sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor, provides a comprehensive database of worker attributes and job characteristics. It’s particularly useful for mapping high-level ‘occupational’ skills to standard job titles.

- The Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) is considered the global gold standard for IT and digital skills. It provides seven levels of responsibility and detailed descriptions for specialized technical skills, defining ‘software engineering’ with high precision.

- European Skills, Competencies, and Occupations (ESCO) is a multi-lingual framework that bridges the gap between the labor market and education. ESCO is useful for global organizations as it provides standardized terminology across 27 languages, making it easier to align skills across international borders.

Example 3: Internal talent marketplaces

- As more companies embrace agility, the internal ‘gig economy’ is replacing rigid hierarchies with a fluid approach to using key skills. This shift means the boundaries of traditional departments are giving way to a more dynamic ‘skills-based’ structure.

- Internal talent marketplaces rely on ontology-based ‘skills graphs’ to connect people to more than just permanent roles.

- By linking specific abilities to ‘gigs’, high-priority sprints, and mentors, organizations can staff critical projects in days rather than months. This ensures the right expert is always matched to the right task, regardless of their official department.

Example 4: Learning recommendation engines

- Learning experience platforms (LXP) use ontologies to map content to specific proficiency gaps

- For example, if a user’s assessment shows a gap in ‘strategic negotiating’, the ontology ensures they receive content specifically for that skill, and updates the recommendation as their proficiency score improves.

Example 5: Skills-based hiring models

- Forward-thinking companies are switching from formal qualifications to mapping necessary skills directly to job requirements, interview scorecards, and technical assessments.

- By using an ontology to define exactly what a role requires, they reduce over-reliance on traditional degrees or past titles, leading to more diverse and capable hires.

Example 6: Customer support capability maps

- Contact centers use ontologies to tie specific product knowledge, compliance, and communication skills to quality and performance metrics

- This allows managers to pinpoint exactly which issue-resolution skills are lacking when a specific KPI, such as ‘first call resolution’, begins to dip.

To sum up

By moving beyond static job titles and embracing a dynamic, interconnected map of abilities through a skills ontology, companies can improve internal mobility, hiring accuracy, and learning effectiveness. This, in turn, allows them to reach new levels of industry competitiveness.

Ultimately, a skills ontology is more than just a technical tool — it’s the strategic foundation of a skills-based organization, providing a common language and the intelligence needed to ensure your talent strategy is as agile and adaptive as the market itself.